CNN – A Republican-led investigation into the origins of Covid-19 has unearthed additional, though circumstantial, evidence supporting the theory that the virus likely escaped from a lab in Wuhan, China, but it did not find any “smoking gun” evidence to prove the theory, according to a new report released on Wednesday.

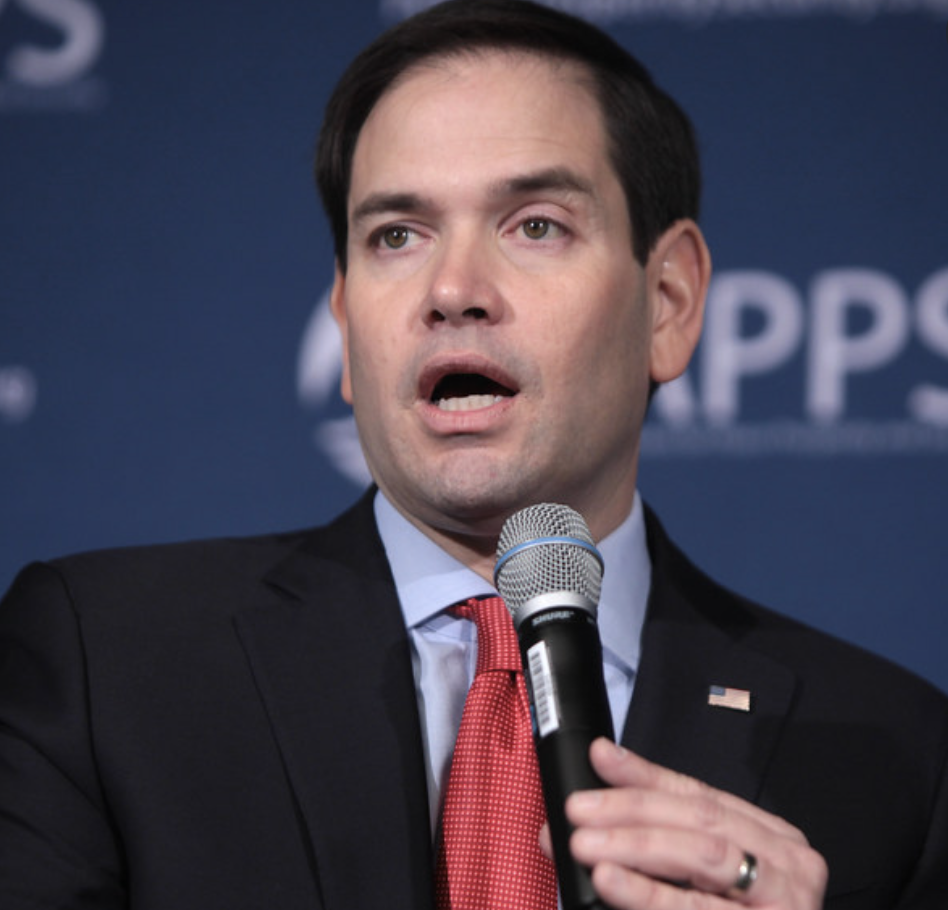

Sen. Marco Rubio, the top Republican on the Senate Intelligence Committee, initiated a probe into the origins of Covid-19 nearly two years ago and the report released Wednesday by his office argues that new information discovered by congressional investigators adds to the credibility of what is known as the “lab leak theory.”

At the same time, the report acknowledges that Rubio’s probe did not unearth “smoking gun” evidence proving the virus emerged from a laboratory accident rather than emerging naturally in the wild – echoing what top US intelligence officials told lawmakers earlier this year about how there are still conflicting views about the true origins of the pandemic.

The summary of Sen. Rubio’s mammoth 300-page report — itself more than five pages long — appears below.

SUMMARY OF FINDINGS

From the report “A COMPLEX AND GRAVE SITUATION”: A POLITICAL CHRONOLOGY OF THE SARS-COV-2 OUTBREAK by Senator Marco Rubio and staff

This study identified a variety of significant indicators that the PRC [People’s Republic. of China] authorities and relevant figures in the scientific community possessed some level of awareness of an outbreak of infectious disease well in advance of the first disclosure of this information to the public on December 31, 2019.

Information detailed in this report, including that derived from official Chinese sources, further indicates that a serious biocontainment failure or accident, likely involving a viral pathogen, occurred at the state-run Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) during the second half of 2019 – approximately during the same period of time in which the available epidemiological evidence indicates that SARS-CoV-2 was introduced to the human population in Wuhan.

In addition, indirect evidence suggests that the most senior leadership of the CCP likely had at least limited knowledge of this laboratory incident by no later than the middle of November 2019.

This incident occurred within a climate of intense political pressure on the CAS to stand up the WIV’s new flagship BSL-4 laboratory complex, the first of its kind in China, and to produce technological breakthroughs in short order that would free China of its so-called “stranglehold” problem.

Awareness of a laboratory incident seemed to have shaped the CCP leadership’s response

to SARS-CoV-2: a response characterized by strict controls of information, obfuscation,

misdirection, punishment of whistleblowers, and the destruction of key clinical evidence.

A closer look at the early days of the pandemic revealed that even when Beijing shared

information with the international community – such as the initial notice of a pneumonia

outbreak, the later admission that a novel coronavirus was its causal agent, and the

publishing of its genomic sequence – it did so belatedly. In all three cases, Beijing

possessed the relevant information for some time before sharing it, and disclosed it only

when compelled to do so by circumstances beyond its control.

Awareness of a laboratory incident also seemed to inform Beijing’s launch of a quiet, but

determined, regulatory campaign in 2020 to strengthen biosafety practices nationwide.

This campaign, documented here for the first time, was not incidental to, but rather wasoften billed as part of the package of emergency measures that PRC authorities were

implementing to halt or slow the spread of COVID-19.

This muscular and sustained campaign to regulate laboratory safety practices in 2020 and 2021 further stood in contrast to the showy, but seemingly insubstantial, measures that were taken in early 2020 to regulate wet markets – the most likely site where a zoonotic spillover could have occurred.

Beijing’s regulatory campaign was also discordant with its public statements to the

international community that portrayed the prospects that the pandemic began as a

result of a laboratory-acquired infection as extremely low, dismissing all suggestions to

the contrary as farfetched, even conspiratorial.

Such dismissal contradicted prepandemic statements made by the PRC Ministry of Foreign Affairs and senior officials of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) who warned on multiple occasions that technological advances in synthetic biology were increasing the risk of a devastating lab leak.

Before the pandemic, Beijing saw nothing conspiratorial at all about considering

the real risks that a laboratory escape of a dangerous pathogen could pose to public

health. In fact, it called for measures to prevent such a scenario. Even after the outbreak,

major differences were observed between how Beijing communicated internally to

officials responsible for biocontainment laboratories and how it messaged externally to

the Chinese public and the international community.

Just as Beijing was dismissing the lab leak theory of the origin of COVID-19 in international settings, internally, Beijing was warning its officials that the risk of laboratory-acquired infections with SARS-CoV-2 was significant, and ordering regulatory reforms to be implemented immediately to improve laboratory biosafety conditions. These biosafety regulatory reforms were rolled out in a manner that was concerted, systematic, and top-down, with Hubei provincial and Wuhan municipal authorities, among others, taking steps to carry out Beijing’s directives in 2020 and 2021.

The WIV also filed three patents between late 2019 and 2021 that looked like remedial measures addressing three different avenues by which an airborne pathogen could infect researchers in a laboratory setting. These innovations that the WIV sought to patent were technical solutions to specific biosafety problems, including those that WIV authors explicitly described as posing a serious risk for the escape of a highly consequential pathogen into the external environment.

A careful reading of reports from the WIV spanning more than a three-year period yielded a picture of a struggling institution: underfunded, underregulated, and understaffed. WIV leadership complained that some portion of their overworked staff was also poorly trained, while some reports revealed a work culture of laxity toward safety matters and described difficulties adapting to the work environment at their newly constructed facilities.

Persistent problems popped up month after month in report after report, casting considerable doubt on the WIV’s claims of successful remedy. By their own admission, WIV researchers conducted experiments involving SARS-like coronaviruses, prone as they are to airborne transmission, in BSL-2 laboratory conditions with the relatively negligible protections required of researchers at that biosafety level.

The WIV was almost an accident waiting to happen, and it appears that an accident, or perhaps accidents, did happen, and roughly concurrent with the initial outbreak of SARSCoV-2.

Beginning in late 2018 and building like a crescendo throughout the months of 2019 that preceded the initial outbreak in Wuhan, a series of reports from the WIV indicated that inspections had identified “hidden dangers,” “shortcomings,” “nonconforming items,”

and various biosafety “problems” that were described alternatively as “foundational,”

“critical,” and even “urgent.” CCP cadres spoke of a rough start for the WIV’s new BSL4 laboratory complex in which they suffered from “no equipment and technology standards, no design and construction teams, and no experience operating or maintaining [a lab of this caliber].”

In late July 2019, WIV leaders warned of “urgent problems we are currently facing,” and by November, they “pointed to the severe consequences that could result from hidden safety dangers.”

WIV researchers labored under the shadow of a political imperative to reduce reliance

on imported “key and core equipment” in order to address China’s so-called

“stranglehold problem.” The CCP leadership constantly impressed on WIV management

their duty to produce scientific breakthroughs that would fuel “indigenous innovation,”

and assigned some portion of its staff to projects that were classified as state secrets.

With unreasonable expectations that they must propel China to the forefront of the field

in short order, compounded by the inherent pressures of working on secret projects for

political overlords who also demanded that they reverse engineer essential equipment,

or otherwise find technical workarounds just to avoid importing equipment from abroad,

one could surely forgive WIV researchers if they faltered or failed.

Scientists should not have to toil under such unfavorable conditions, but they did in Wuhan, and no doubt still do.

Counter to what one might expect, the political clock of SARS-CoV-2 began ticking

before the epidemiological clock. In other words, Beijing was not just cognizant of the

risk of a sudden outbreak of an infectious respiratory disease before it happened, but to

some extent, it was preoccupied with guarding against this risk, especially as it pertained

to biocontainment laboratories.

For whatever reason, the authorities appeared to be preparing for what eventually happened well before, or just before, it happened. For example, at the top leadership’s behest, the national legislature started working in earnest on biosecurity legislation in July 2019 that they had previously deemed a relatively low priority. Some of this preoccupation with preventing outbreaks of infectious disease can be attributed to the legacy of the SARS-CoV-1 epidemic of 2003, but as the reader will soon see, other elements are harder to explain with an appeal to history.

Once the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak was underway, political prerogatives likewise

set the cadence for the medical countermeasures that would follow. Three years have now passed since the outbreak of a “pneumonia of unknown origin” became public knowledge. In that time, Beijing has displayed an uncharacteristic lack of seriousness toward determining the origin of the disease; the CCP is usually keen to snuff out sources of political and economic instability, and their actions have left no doubt that they regard COVID-19 as a major threat to stability.

Beijing has further shown a tendency to resort to highly implausible claims about the origin, asserting it began anywhere other than China (often claiming it came from military laboratories in the United States). To further confuse the situation, Beijing has indulged in fantastical theories, such as the idea that the virus was imported to China through frozen seafood.

Meanwhile, it has reacted to the actual outbreak on the ground with excessive

seriousness and resolve, as if it confronted not merely a public health emergency, but

rather a political crisis with the potential to shake the very pillars of one-party rule.

The inconsistency between Beijing’s urgent and aggressive reaction to the outbreak itself

and its lackluster efforts to ascertain the virus’s origin – alas, its policy has been to

actively frustrate international efforts to identify the origin and to punish PRC citizens

who try to investigate on their own – suggests that Beijing already knows the origin, and

fears that public confirmation of the origin could precipitate an existential crisis for the

CCP and therefore must be avoided at all costs.

The failure of local authorities to regulate the trade of wildlife at wet markets giving rise to the zoonotic spillover of a novel human pathogen is a crisis that the CCP has weathered before. There is no reason to believe that they could not survive it again.

Risky research conducted at a state-run laboratory having inadvertently unleashed a

novel pathogen, which then set in motion a once-in-a-century pandemic of almost

unimaginable devastation, is a decidedly different and unprecedented problem with a

path of culpability that leads unquestionably back to Beijing. When one further

considers that this state-run laboratory was built to showcase China’s growing scientific

prowess, and at least some segment of its research involved state secrets, it is not hard

to imagine the extreme embarrassment and sensitivity that such a scenario would elicit

in CCP leaders, even if the accident had not precipitated a pandemic.

Needless to say, we do not yet know with complete certainty that a biocontainment failure was responsible for the first human infection of SARS-CoV-2, but what we present below is

a substantial body of circumstantial evidence that supports the plausibility of such a

scenario.