THE NEW YORK TIMES – In January 2018, a female crocodile in a Costa Rican zoo laid a clutch of eggs. That was peculiar: She’d been living alone for 16 years.

While crocodiles can lay sterile eggs that don’t develop, some of this clutch looked quite normal. And one of them — in a plot twist familiar to anyone who has watched “Jurassic Park” — continued to mature in an incubator. In this case, life did not, uh, find a way, as the egg eventually yielded a perfectly formed but stillborn baby crocodile.

In a paper out Wednesday in the journal Biology Letters, a team of researchers report that the baby crocodile was a parthenogen — the product of a virgin birth, containing only genetic material from its mother.

While parthenogenesis has been identified in creatures as diverse as king cobras, sawfish and California condors, this is the first time it has been found in crocodiles.

And because of where crocodiles fall on the tree of life, it implies that pterosaurs and dinosaurs might also have been capable of such reproductive feats.

Here’s how a virgin birth happens: As an egg cell matures in its mother’s body, it divides repeatedly to generate a final product with exactly half the genes needed for an individual.

Three smaller cellular sacs containing chromosomes, known as polar bodies, are formed as byproducts.

Polar bodies usually wither away. But in vertebrates that can perform parthenogenesis, one polar body sometimes fuses with the egg, creating a cell with the necessary complement of chromosomes to form an individual.

That’s what appears to have happened in the case of the crocodile, said Warren Booth, an associate professor at Virginia Tech who has studied the eggs … Image

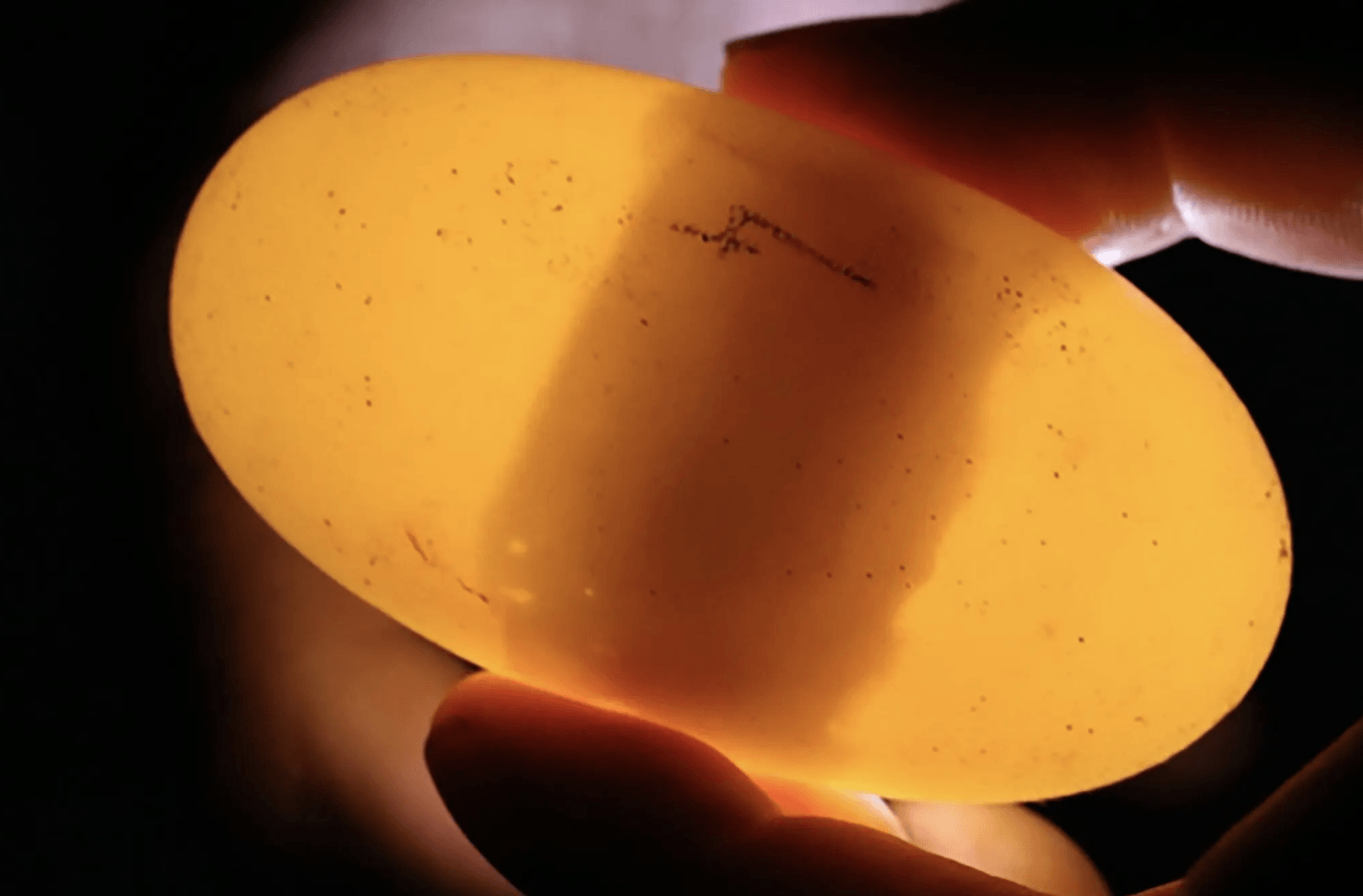

A close-up view of an illuminated yellow egg, held between two fingers with a dark band across the middle and the number 4 written on the egg’s surface.

IMAGE: Quetzal Dwyer