Lisa Farris worried that a nasty infection from recent liposuction and a tummy tuck was rapidly getting worse. So she phoned the cosmetic surgery center to ask if she should head to the emergency room, she alleges in a lawsuit.

The nurse who took the call at the Sono Bello center in Addison, Texas, told her she “absolutely should not” go to the ER — even though Farris “had a large gush of foul fluid” leaking from the incision, according to records in the malpractice case she filed against the cosmetic surgery chain in 2024.

The nurse told Farris she “only needed to reinforce her dressing to collect the fluid drainage and give it time,” filings in the lawsuit alleged.

“Thankfully, Ms. Farris did go to the ER where she was diagnosed with sepsis from her surgery complications,” a medical expert for her legal team wrote in a court filing. Left untreated, sepsis can lead to death.

Sono Bello officials declined to discuss malpractice cases filed against the company, citing patient privacy laws. But in court filings, the company has disputed Farris’ claims. The case is set for trial early next year.

The Farris lawsuit is one of dozens of medical malpractice cases filed over the past three years that accuse cosmetic surgery chains of failing to provide adequate care for patients in the days and weeks after their procedures — in many cases by allegedly neglecting to promptly treat painful infections and other serious complications — including for four patients who died, a KFF Health News investigation found.

In some cases, patients who traveled hundreds of miles or more for seemingly routine surgeries allegedly suffered painful complications while recuperating in hotel rooms or unlicensed “recovery homes,” which they said lacked adequate medical staff and supervision, according to court filings.

While complications, such as infections, can occur after any surgical procedure, problems related to postoperative care are blamed for contributing to injuries in over two-thirds of the cosmetic surgery cases KFF Health News reviewed.

The surgery companies involved — some, like Sono Bello, financed by private equity investors — offer elective procedures such as liposuction and “Mommy Makeovers” to patients who pay thousands of dollars out-of-pocket or on credit. Ads promise life-changing body reshaping techniques with minimal risk and quick recovery times.

Medical malpractice lawsuits have trailed behind the growth of these companies. Suits have accused the chains of hiring doctors who lacked adequate training or had troubled pasts, and of using high-pressure sales tactics and misleading advertising pitches that downplay safety risks, court records show. The companies dispute these allegations and have won dismissal of some suits.

Patrick Schaner, a plastic surgeon and a Sono Bello medical director, stressed that the company has performed more than 300,000 cosmetic operations with minimal complications. “That context is very important,” he said in an interview.

Schaner said Sono Bello surgeons are “good at what they do” because of the large numbers of procedures they perform. “We do a great job of getting safety protocols in place,” he said.

Many patients who file lawsuits blame disfiguring injuries on what happened after their operations, such as office visits in which medical staff allegedly didn’t recognize, or dismissed, evidence of worsening surgical complications, court records show.

A nurse at a Sono Bello center outside Chicago allegedly failed to alert doctors when Mary Anne Garcia, a patient who had had liposuction at the center about three weeks earlier, showed up there with her aunt. Garcia was dizzy and so weak she required a wheelchair to get back to the car, according to a lawsuit her estate filed in September.

Rather than tell Garcia to go to an emergency room, the Sono Bello nurse told her to “drink more fluids and try to eat something,” according to the complaint.

Garcia died the next day from cardiac arrest, according to the lawsuit. Sono Bello has yet to file a response to the lawsuit in court.

‘It Was Horrifying’

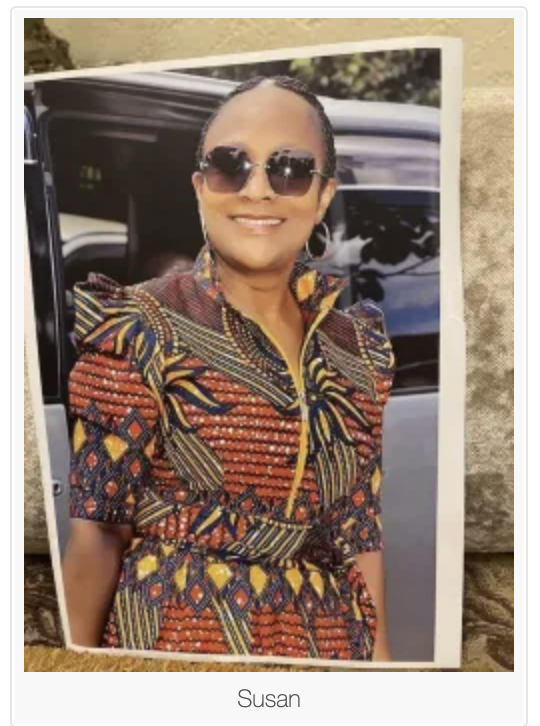

Susan Easley, 59, a veteran U.S. Agency for International Development executive who spent two decades working on AIDS projects in Africa, died in a Washington, D.C., short-term apartment last year.

Her son Gavin found her body May 13, 2024, four days after she had an AirSculpt liposuction and fat transfer operation at Elite Body Sculpture in nearby Vienna, Virginia, according to a lawsuit filed in November.

“It was horrifying,” Gavin Easley told KFF Health News in an interview. “My mother was the definition of kind, caring, and unconditionally loving. She was the most incredible woman I’ve ever known,” said Easley, 29, who runs an organic farm in Arkansas with his wife.

The suit alleges that surgeon Dare Ajibade gave Easley an excessive amount of the anesthetic lidocaine during the 6½-hour procedure and failed to recognize persistent vomiting afterward as a sign of toxicity. She called the clinic to report her condition, but her concerns were dismissed, the suit alleges.

“When she called to report complications, they didn’t take it seriously,” said Virginia attorney Peter Anderson, who filed the suit. He said Easley presented “clear signs and symptoms” of problems.

AirSculpt is a brand of Elite Body Sculpture, a Miami Beach-based chain founded by cosmetic surgeon Aaron Rollins. The company, which is financed by private equity investors, has about 30 branches across the country. Neither the company nor Rollins responded to repeated requests for comment on patient lawsuits. In court filings, the company has denied the allegations.

Ajibade has since relocated to Texas, where he works for Sono Bello in San Antonio, according to the company. Neither the surgeon nor the Virginia surgery office, which is also a defendant in the case, returned calls for comment. The defendants have yet to file an answer in court.

A Booming Business

Sono Bello, with more than 100 centers nationwide, bills itself as “America’s #1 Cosmetic Surgery Specialist.”

Patients filed seven malpractice cases against Sono Bello in September — each in a different state. In an interview, Marcy Norwood Lynch, a Sono Bello executive vice president and chief legal officer, speculated that the spurt in cases was related to reporting by KFF Health News and NBC News about the company. There “could be alignment” between the coverage and the filing of the suits, she said. The company has denied the allegations in court.

KFF Health News reviewed a sample of more than 100 medical malpractice cases filed against multistate surgery chains from the start of February 2023 through November 2025. Malpractice suits do not by themselves prove substandard care, though many medical authorities and licensing boards consider them a tool for helping to judge medical quality.

Heather Faulkner, a plastic surgeon and associate professor at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, said surgeons must quickly recognize signs of infection before they progress and become serious, even life-threatening conditions.

At Emory, she said, surgeons must attend their patients’ first visit after cosmetic surgery. “Ultimately, the physician is the one responsible,” she said. “The patient has to be seen by the person who did the operation and knows how to recognize something is wrong,” Faulkner said in an interview.

Patients suing cosmetic surgery chains often argue that they were seen by nurses or other staff members who, they allege, lacked the training to recognize and deal with problems before they required emergency wound care.

Schaner, the Sono Bello medical director, said the company has a phone messaging system that ensures patients can get in touch with their surgeon or other company physicians. While nurses see some patients, the “ultimate decision-making is passed to the surgeon,” he said.

Five patients treated at Sono Bello centers who sued the company during 2025 alleged that surgical wound complications were dismissed after medical staff, including surgeons, viewed pictures of the injuries, court records show. The cases are pending.

Schaner said Sono Bello sometimes has patients submit photos of wounds but the images are “not the sole means of triage” of patient injuries or complications.

Joshua Kiernan sued Sono Bello after having liposuction on May 28, 2024, at the branch in Columbia, South Carolina. On June 8, 2024, he stumbled and fell in a gym parking lot, causing drainage around the incision in his stomach, according to the suit. On June 17, 2024, Kiernan visited the office complaining of “redness and pain” around the incision, according to his suit.

The surgeon, Stancie Rhodes, didn’t examine him in person but had an office staff member take a picture “so that she could view it from another part of the office,” according to the complaint.

The surgeon sent back word that the photo “looked fine,” and Kiernan was told to take Tylenol for the pain and follow up at the office a week later, the complaint alleged.

Two days before his appointment, Kiernan required emergency hospital treatment for “abdominal hematoma and infection,” according to the suit.

Kiernan underwent six surgical procedures and ran up medical bills of more than $325,000 to treat his condition, according to the suit. In court filings, Sono Bello denied the allegations.

“Surgical care does not end at the last stitch,” said Mark Domanski, a plastic surgeon in Virginia, who believes the chain clinics in general are more adept at marketing than providing patients with top-notch care. “It involves postoperative visits with the surgeon who did the procedure, who is there to respond to the patient’s concerns, questions, especially if things are not going well,” he said.

Recovery Houses

Many patients who travel for cosmetic surgery, either to save money or because services aren’t available in their area, can’t return home right away.

Yet there’s little agreement on where patients should recuperate, for how long, and what medical services should be readily available to them.

Scott Hollenbeck, immediate past president of the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, said laws or regulations in most states don’t spell out requirements.

“This can create a wide variation of oversight, staff qualifications, and available medical support,” he said.

The plastic surgery society has warned against a cottage industry of recovery houses that often charge patients hundreds of dollars a night while they recuperate, even though they may lack medical staff capable of handling possible surgical complications.

Court filings in Florida show patients staying in recovery houses and hotels have died or suffered untreated complications, mostly in South Florida, where officials have struggled for a decade or more to regulate unlicensed facilities. One local lawmaker recently filed a bill to rein them in.

Hollenbeck said patients who recuperate in a hotel or other facility need to find out in advance what “level of care” will be available. He said ads touting “luxury” accommodations or “conveniently located” do not make a hotel “clinically qualified to provide recovery care.”

Easley, whose mother died in Washington, D.C., said he is struggling to understand what happened after a medical transportation service took her from the Virginia surgery center to a temporary apartment.

He said his mother, who was born in a small village in Uganda before emigrating to the U.S. as a teen and joining the U.S. Army, “had so many plans” for the future.

Susan Easley had been medically cleared for a new assignment in Africa. After that, she planned to retire and start a farm in Tanzania, among other things, according to her son.

The lawsuit alleges the surgery center discharged her prematurely given signs of a dangerous condition called local anesthetic systemic toxicity caused by an overdose of lidocaine.

Susan Easley called the surgery center that day and reported “multiple instances of nausea and vomiting,” but there’s “no evidence” that anyone told her to head to an emergency room, according to the suit.

“I don’t know what they said to her,” Gavin Easley said. “It’s a horrifying thought for me. I have no idea how to get to the bottom of that mystery.”

‘Preventable Death’

Some lawsuits take aim at decisions made by support staff members, who help monitor patients after surgery.

That’s a critical issue in the case of Mary Anne Garcia, the Illinois woman who died after her aunt drove her to the Sono Bello office in Oakbrook Terrace, Illinois, on June 4, 2024.

Garcia “was feeling sluggish, dizzy, and nauseated,” according to the suit. She also had a rapid heartbeat and low blood pressure, according to the complaint. But registered nurse Lucia Raddatz did not notify the surgeon or urge Garcia to seek emergency care even though Raddatz had to help her back to the car in a wheelchair due to Garcia’s “severely weakened condition,” according to the suit.

Filed on behalf of Garcia’s estate, the suit names Raddatz and Sono Bello as defendants. An emergency room physician hired as an expert in the case opined that had Garcia gone to the emergency room on June 4, “she would have received care which would have avoided her death,” court records state. Sono Bello had no comment and has yet to file an answer in court.

Established plastic surgeons say they are often called upon to treat patients who arrive in the emergency room with complications because surgeons working for the chains may lack local hospital privileges or are otherwise not available for consultations.

“There is not one colleague of mine who has not dealt with the complications of these types of facilities or med spas on more than one occasion,” said Charles Pierce, president-elect of the New Jersey Society of Plastic Surgeons.

‘Angry and Betrayed’

Doctors at an Austin, Texas, hospital expressed such frustration while caring for Anna Palko, a 33-year-old mother of four, according to a malpractice suit she filed in November against surgeon Rambod Charepoo and his employer, Mia Aesthetics. The Miami-based cosmetic surgery company, which operates in about a dozen cities, including Austin, advertises that it delivers the highest quality of plastic surgery at affordable prices.

A doctor at St. David’s Medical Center in Austin wrote in Palko’s medical record: “Unfortunately patient has had postoperative complications from a physician who is well-known to our emergency department for similar post-op complications associated with cosmetic surgery through MIA (sic) Aesthetics,” according to the suit.

Palko is one of five Texas women who sued Charepoo and Mia Aesthetics for malpractice this year, between mid-July and the end of November, court records show.

Four women allege the surgeon and the company failed to adequately treat infections that developed after surgery, while the fifth alleged other complications. Mia Aesthetics was dismissed from one case. The surgeon and the company have denied the allegations in court filings, court records show.

Charepoo also has been the subject of a lengthy investigation by the Texas Medical Board, which licenses doctors.

In August 2021, the board alleged that the surgeon “failed to meet the standards of care” in treating six patients, including one he placed “at risk” by allowing the patient to leave the surgery center for the emergency room in a private vehicle after the person “experienced significant hypotension and hemorrhagic shock.”

In October 2024, the medical board found that Charepoo had failed to meet standards of care for five of the six patients. The board required him to have a surgical proctor oversee 20 of his operations per quarter for two years. The board also ordered him to take medical education courses, pass an exam, and pay a fine of $4,000.

Charepoo is fighting the order in court. Charepoo, Mia Aesthetics, and lawyers representing Charepoo and the company did not respond to requests for comment.

In January, he sued the Texas Medical Board, arguing the penalty is “both excessive and unjustified” and should be invalidated. The medical board declined to comment on the suit, which is pending in Travis County District Court.

Hearing of the surgeon’s problems came as a shock to patient Palko, who said she had chosen Mia Aesthetics because of ads promising high-quality doctors.

“I felt so disgusted, angry, and betrayed,” Palko said in an email sent through her attorney.

Have you had liposuction, a “Mommy Makeover,” a tummy tuck, a Brazilian butt lift, or another type of cosmetic surgery? We’d like to hear about your experience. Click here to contact our reporting team.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

Subscribe to KFF Health News’ free Morning Briefing.

This article first appeared on KFF Health News and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()